Transcript of Preventing the collapse of civilization

Preventing the collapse of civilizacion is a talk that Jonathan Blow gave on May 2019 during the DevGamm conference held in Moscow, Russia.

It is a polemic and pretty candid talk about the current state of the Software industry and its possible decline. You can agree or not with Jonathan's arguments, but you can't remain indiferent to them.

With the goal to preserve it, we've transcribed it and added subtitles. If you find any error, feel free to send a Pull Request.

We also have translated it to Spanish, you can find the translation here.

Transcript

link

00:00:04

Then, when it came to giving a talk, it's made me think about some things that transpired between both of our societies some decades ago. For example, in 1957 when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world's first man-made satellite that orbited the earth successfully. Back in the USA, everybody freaked out about this.

They didn't like being behind in space, and said "Oh my god, we got to catch up. We have to get a satellite into orbit in 90 days". Which seems crazy and it was. Our first attempt blew up on the launch pad. But the second attempt succeeded, that was January 31st 1958. It was almost a hundred and twenty days after that initial launch. It was pretty fast by modern standards.

Then, in April 6 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to orbit the Earth, and again that made news all over the world. Everybody was very impressed by that, and back in the United States people were upset because again we were behind. We were behind in what was becoming clear was the space race, and we didn't like that.

And what were we gonna do about it?

link

00:01:17

So in late May 1961, one month after that flight, our president at the time, Kennedy, made a speech to Congress saying like, look if we're gonna catch up and not be behind forever, we have to do something big. We have to commit a lot of money, a lot of resources. We're gonna go to the Moon, right? And that was kind of a crazy idea. And in 1962 he reiterated this in a famous public speech and he said, look we're gonna go to the Moon before the decade is over, and that was crazy.

link

00:01:46

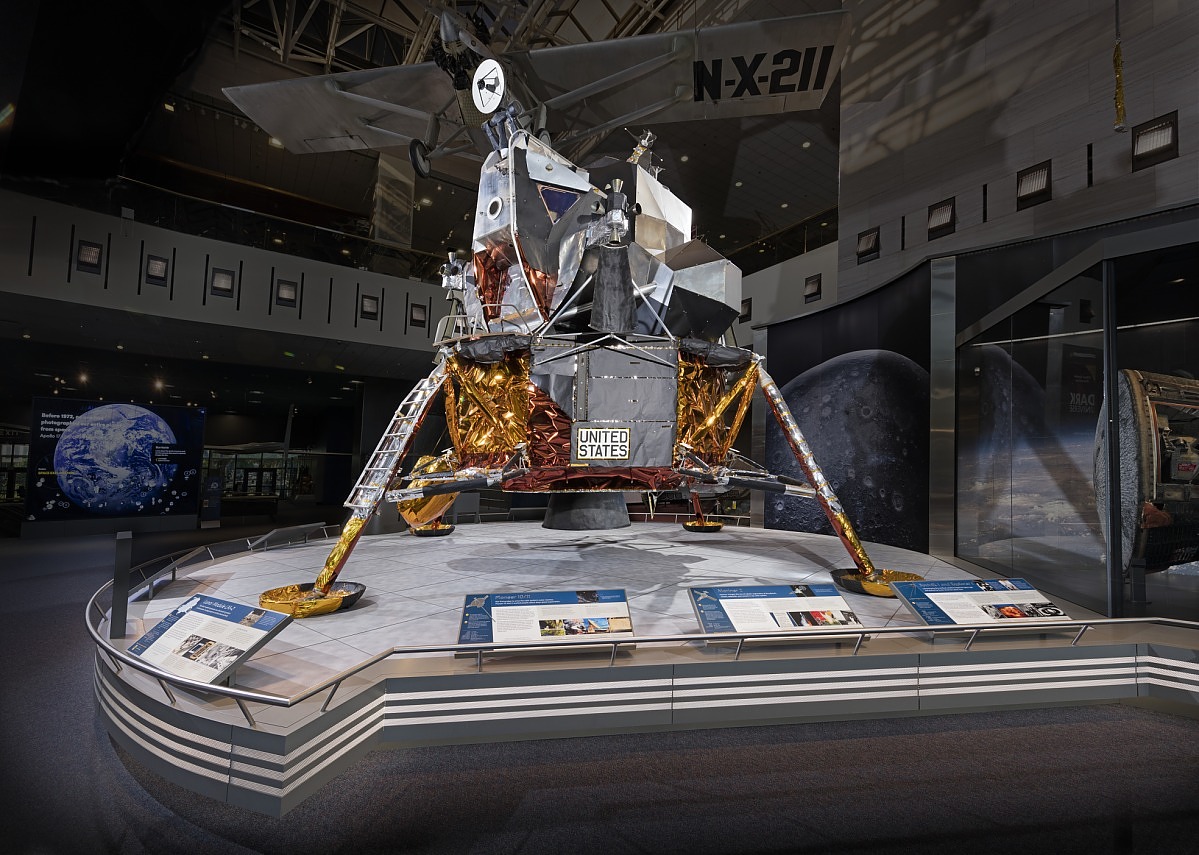

It was really crazy because we haven't done anything remotely like that. But lo and behold, eventually we did. So Apollo 11 launched on July 16th 1969, before the decade was over, and just this year there's a very good documentary that came out about this whole mission What it is? It's made of all original footage that NASA took during the mission, that's been sitting away in cupboards and closets, and they restored the footage and they sort of made a recreation of what it was like to live through this mission, and I'm gonna play a short excerpt from that documentary, just to give you a sense of what the scale of this whole thing was like.

link

00:03:22

It's a lot and it's crazy we went from nothing to all that stuff, in something like 12 years. Before Sputnik flew, we didn't have much of a space program in the United States, and in the end we had all that stuff. And then of course, after that we continued to do space things, right?

link

00:03:38

We made this Space Shuttle. It seemed like a really cool thing. It's like a ship out of science fiction. It could like, take off and then land again that's so great, right?. The problem is actually most of it couldn't land, like those tanks in the background there, and therefore, it was very expensive to fly and it was very unreliable. People died on this on a couple of different missions and we decided to stop using it for all these reasons. So, after that if we wanted to put people in orbit, we had to get a ride on the Soyuz and then from there the trajectory of our space program kept going downwards. And so if you talk to somebody like me sometime around the year 2002 or 2005, we all had this attitude like, isn't it a shame? Like the USA used to do all this cool stuff in space and now we like don't really do anything.

link

00:04:27

And the science fiction future that we visualized isn't really going to happen, and we don't even see that changing and but what can you do about it? Oh well, shrug, right? That was just everybody's attitude. But not quite everybody right. At some point, somebody came along who made a bunch of money on a website and said: Hey I want to do something about this. Despite having no rocket experience I'm gonna start a company to launch rockets and to do bigger stuff than we've ever done before.

link

00:04:59

And so here's an excerpt of a video about why he did that stuff Elon Musk: Then there's becoming a multiplanet species and space-faring civilization. This is not inevitable. It's very important to appreciate this is not inevitable. The sustainable energy future I think is largely inevitable, but being a space-faring civiliazation it definitely not inevitable. If you look at the progress in space, in 1969 we were able to send somebody to the moon. 1969. Then we had the Space Shuttle. The space shuttle could only take people to low Earth orbit.

Then the Space Shuttle retired and the United States could take no one to orbit. But so that's the trend. The trend it's like down to nothing. People are mistaken when they think that technology just automatically improves. It does not automatically improve. It only improves if a lot of people work very hard to make it better, and actually it will, I think, by itself degrade, actually. You look at great civilizations like ancient Egypt, and they were able to make the Pyramids, and they forgot how to do that. And the Romans they built these incredible aqueducts. They forgot how to do it.

link

00:06:24

Jonatahan: So, his idea was pretty successful and today we're like landing rockets and we're seriously talking about doing another moon mission as soon as the Year 2024. We'll see if that actually happens. But really talking about it seriously and that's a pretty good thing given where we were not long ago.

So, Elon talked about a few things from the past that were great achievements that have been lost, and I want to go through a few more of those to reiterate his point that technology automatically degrades.

link

00:06:52

This thing here that you see is the Lycurgus cup. This was a relic found and dated back to the Roman Empire: 380 A.D. And it's made of glass and this glass that it's made of is the world's earliest known nano material. Okay? The color of the glass changes based on how you look at it. Where the light source is. So, if you're looking at it standing in front of the glass, and the light source is sort of over here with you, so that you're seeing it with reflected light, then the Goblet is green. But if light is passing through, it the Goblet is red.

They had this in 300 A.D. right? And then the Roman Empire fell and that knowledge was lost until basically forever.

The way this worked was actually, you know, it got figured out around 1990. The glass is suffused with very small particles of silver and gold. By very small, I mean 50 to 70 nanometers. Which is so small you would not be able to see them with a physical microscope. You would require an electron microscope to see these particles, right?. But at some point the Roman Empire fell and they forgot how to do it.

A lot of craftsmanship went into this. You can see, you know, how its hollowed out on the inside where the little guy's body is to give him more of a purple sheen, as opposed to a red in the background

link

00:08:14

And if you hear people talk about this today or you read up on this, they can have a dismissive attitude toward it, like "Oh, the stupid Romans didn't understand technology. They probably didn't even know it was silver and gold that made this happen. It was probably just an accident and they made like five of these" right? Which is complete nonsense. Like. anybody who actually builds things as opposed to just writing about them, knows you do not get a result this good without a constant process of iteration and refinement. You can imagine there will be some initial accident, like maybe somebody wanted to make glass sparkly and they tried to put silver and gold in it, and then they noticed a little bit of discoloration. And they said, like, why is that there? And maybe they pursued that.

Like, what happens when I change the proportions? How thick should the glass be? Like, engineering results this good takes a long time, and what that means is that in Rome people were doing something that we would recognize today as materials science. And then that was lost.

link

00:09:17

Other stuff happened. Like, in the Byzantine Empire, they had flamethrowers, and not like little dinky things. They had giant pressurized vessels in the bellies of ships that shot out a napalm like substance out of metal tubes that they would use to incinerate neighboring vessels. It was napalm-like in the sense that water would not put this fire out, right? It was a very serious weapon. It was a state secret of the Byzantine Empire. They used it to defend Constantinople over and over again for hundreds of years, until one day they couldn't really do that anymore, for whatever reason, and this military secret just faded from knowledge. Nobody knows how to do it now. Obviously we've reinvented flamethrowers, but they're different.

link

00:10:01

But this is the Antikythera mechanism, which is named after an island in Greece where this was found on a sunken ship. It was just a corroded hunk of metal or a number of corroded hunks of metal. But it was very clear, when they were originally discovered, that gears were involved and over time people analyzed this. They realized it's a mechanical calendar that was used to say things like you know what what year is it, what are the phases of the Moon, where are the planets going to be right now, when is the next Olympic Games, right? And people have run scans on on what is left of this and managed to deduce what all the gears were in this mechanism. And it's very different from what I thought.

When I first heard news about this, I thought like oh they must have had some cute little gear things in Greece, that's surprising. But let me just show you the scale of the generally agreed upon reconstruction of what this device actually was.

That seems like a lot of gears, right? But wait, there's more. So ancient Greece had that. But that is not the picture that we have today of ancient Greece, right? And the thing to realize is: You don't just get here from nothing. It's not like one day there weren't any gears and then the next day some guy makes this, right? You need a whole process of science to create something that sophisticated.

And we don't know anything about that today, right? All of that was lost. And I could go on and on with examples. There's a whole bunch of things from history that are like this. But we don't have time.

link

00:12:32

I'm just want to restate that, right now, we live in a very privileged time. Where technology has been in a good shape for a long time. We see it getting better and so we imagine that the natural course of history is that technology always improves,and that these moments in history are just like little blips or something that we heard about. But they're not just little blips. It's actually sort of the regular course of world history that great achievements in technology just get completely lost, because the civilizations that made those achievements fell or, you know, have this sort of a soft fall, where they fail to propagate the knowledge into the future, right?

Technology goes backward all the time and not just in ancient history, also in the modern day, right? We lose knowledge all the time. So, I'm gonna read an excerpt from an interview with Bob Colewell, who was the chief microprocessor architect at Intel for a while. But this interview is from before that.

link

00:13:26

It was from the booming days of Silicon Valley, when he worked at a startup called MultiFlow. They were trying to make a very large instruction word processor, when that was a new experimental idea, and they were having a lot of problems. Like, when you try to design the chip you're using components from other manufacturers, and he just couldn't get anything to work reliably.

And he was like, what what the hell, right? So he says: Rich Lething and I made a pilgrimage down to Texas Instruments in Richardson, Texas and we said: "As best as we can tell many of your chips don't work properly. And does this come as a surprise to you?" I half expected them to say, "What, you're out of your mind. You've done something wrong. Come on, you don't know what you're doing. And go use somebody else's chips" But no, they said "Yeah, we know. Let me see your list" And they looked at the list and said:

link

00:14:14

"Well, here's some more that you don't know about". And by the way, it wasn't just TI. Their parts were no worse than anybody else's. Motorola's were no good. Fairchild's were no good. They all had this problem. And so I asked TI, how did the entire industry fall on its face at the same time? We are killing ourselves trying to workaround the shortcomings in your silicon. And the guy said, "The first generation of transistor logic was done by the old graybeard guys, who really knew what they were doing. The new generation was done by kids who are straight out of school, who didn't know to ask what the change in packaging would do to inductive spikes", right?

link

00:14:52

So when you change the voltage in places on a chip, it generates a magnetic field, because that's just what happens. And when those fields interact across a chip, it's bad right. And, you know. the new people designing these chips didn't know to take that seriously. And that's why technology degrades, or it's at least one reason, right? It takes a lot of energy and effort to communicate from generation to generation these important things that you need to know in order to do a competent job making the technology.

And there are losses in that communication process, almost inevitably. And without this generational transfer of knowledge, civilizations can die.

link

00:15:33

Because of technology that those civilizations depend on degrades and fails. So let's talk about a civilization that fell. Actually, a whole group of civilizations. The diagrams I'm going to show here, are from a lecture you can find on Youtube called "1177 BC, the year civilization collapsed" by Eric Cline. And we're talking about the Late Bronze Age, which was the time of a number of civilizations you've heard of probably. Like the Egyptians or the Mycenaean, Greeks, right? or the Hittites, the Babylonians, and so this civilization or this network of civilizations was sort of spanning Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean Sea. And they had developed quite a sophisticated network of trade.

So in this graph here, each of these points is one of the civilizations and the lines are, you know, established communication and trade routes between those civilizations, and whereas not all of them were connected to all of the other ones, they were interconnected enough that you could relatively efficiently route things from one place to another if you needed to

link

00:16:39

And that was very important because bronze, which the civilization depended on for things like defense, was hard to make back then. You had to do it by combining copper and tin. And copper was relatively hard to find, and was found in places like the island of Cyprus. And tin was also really hard to find and was found very far away from those copper places, like in Afghanistan. And so you saw you somehow had to persistently ship these things around, in order to make your bronze, and the other things that your society depended on.

And nobody's sure exactly what happened in this collapse, but people believed there was some kind of environmental stressor to kick it off. Like, there was a huge drought possibly, also some floods are theorized. And this led to some people attacking some other people. And, you know, maybe you need to start using your ships for defense instead of trading. And, basically, you went from all these flourishing civilizations, to a hundred years later none of them were left. And by none of them were left, I don't even mean that like the nation-states were gone. Like, many of the cities were burned to the ground and the languages and cultures don't survive, even though they wrote by, you know, pressing things into stone. Like, nobody was able to translate those languages. Even today, we still can't translate a lot of them.

link

00:18:04

So, like, so much knowledge was lost here, in this collapse. We'll get back to it later, but so I want to bridge this to the modern day in some way. And my thesis for the rest of this talk is that software is actually in decline right now. It's in, maybe, a soft decline that just makes things really inconvenient for us. But it could lead to a hard decline later on.

Because our civilization depends on software, we put it everywhere. All our communication system are software, our vehicles are software. So you know, we now have airplanes that kill hundreds of people due to bad software and bad software only, right? There was no other problem with those airplanes. Now, I don't think most people would believe me if I say software is in decline. It sure seems like it's flourishing so I have to convince you at least that this is a plausible perspective and that's my goal for the rest of this talk.

link

00:18:55

And what I'll say about that is: these collapses, like we're talking about that Bronze Age collapse, was massive, like all these civilizations were destroyed. But it took a hundred years .So if you're at the beginning of that collapse, in the first 20 years you might think, well, things aren't as good as they were 20 years ago, but it's fine, we're basically the same, right? But then you keep thinking that, you keep thinking that. Every 20 years another couple cities get burned to the ground, and then, eventually, there's like nothing, right?

link

00:19:24

The Fall of the Roman Empire was about 300 years. So, if you're in the middle of a very slow collapse like that, would you recognize it?, would you know what it looked like from the inside? So, of course I expect the reply to what I'm saying to be: "You're crazy, software is doing great! Look at all these internet companies that are making all this money and changing the way that we live, you know?" and I would say: "Yes, that is all happening. But what is really happening, is that software has been free riding on hardware. For the past many decades we've had amazing advances in hardware technology. Computers keep getting faster and faster.

link

00:20:04

It's really one of the greatest accomplishments in human history, that we've somehow managed to do that, and software gets better in air quotes, because it has better hardware to run on. That's the main reason software technology itself has not improved in quite a while, I claim, right? And you can say: "But look at all these examples of cool stuff we can do. Even in the past couple of years so like AlphaGo was an AI that it beated human players at Go". And you can go on, like "Instagram or whatever app and like make your face look like somebody else's face, that's crazy. We didn't used to be able to do that" And that's true. But one, most of these again are products of hardware being fast. Most of these cool things that we do now are due to Machine Learning algorithms and it, you know, those really are relying on quantity of computation right now to produce impressive results. It's hard to imagine being able to train AlphaGo 20 years ago on the computers we had at that time, right? So it's not that... there are software technology improvements here, right? Machine Learning algorithms have legitimately gotten better. But there're two things to say about that. Well, the main thing to say about it, I will say, is just that it's a minority of actual software technology, right? So, of the volume of things that we run, the thing that runs the Machine Learning algorithm that produces the actual impressive result is a very small piece of the program. It's actually really simple, once you understand the math, and, especially if you don't have to train it, if you just have to use it, right?

link

00:21:41

And so when you take an app on your phone like that, that does something funny with your picture, The part of it that does the thing that we think is cool and really value. That piece of software is tremendously simple, compared to all the stuff about like, loading the bitmap for your face or responding to user input events, right? That part of the software is huge and complicated and is the part that's kind of falling apart.

So I would characterize software as having small local technological improvements, like Machine Learning, with overall inertia or degradation in the rest of the field. And we're very impressed by the improvements, though, right?

And let me illustrate the degradation parts as best I can and it's to say that we simply don't expect software to work anymore. And I'm not sure when this happened, you know. Computers always had a reputation for being a little bit funny. But, you know, if you go back many decades ago, it was generally due to like, not being user friendly or hard to understand how to use it. But today, if you're using a program and it does something wrong, you're just like "yeah it's software, restart it whatever". And that didn't used to be. And if our standards are shrinking over time, how low can they shrink before it becomes unsustainable?

link

00:22:58

So, I decided to say, you know, I want to quantify or illustrates how much I put up with this from day to day. So from now on I'm just gonna take a screenshot every time any piece of software that I use has an obvious bug or, you know, unintuitive or incorrect piece of behavior. And, well, I write it, right?

When I decided that I was working on my compiler in the command line and the console that I use, after a while, just start saying "attempt to index a null value" in the prompt, because it's written in Lua for some reason. Then, I go to Emacs and I'm working on my code and Emacs is set to reload files that have been modified and that used to work fine, but at some point they broke it so that it reloads the file too early and doesn't get the whole thing and half of it is cut off. And I have to, like, manually reset that every time it happens.

Then I go to Gmail and I'm going to send an email to the rest of the team about some graphics stuff, making decisions about what to do, and I copy a line of a previous email and paste it into the reply box. And then I start typing my reply and it goes into like a three character wide column over here, because somehow they've managed to reproduce all the kinds of stupid Microsoft Word formatting bugs that everyone was frustrated with in the 90s and 2000's, now those are in Gmail. And I don't know how to fix it.

link

00:24:18

Like, you fight with it for a while to get it to stop happening, you have to like delete something invisible, I don't know. Very annoying. So then I say, okay I'm gonna get some real programming done. I go to Visual Studio and I say I'm going to type in my command-line arguments up there. And, as soon as I do that, we get this box that says "hey, collection was modified, enumeration option may not, your operation may not execute" Why? I don't exactly know why. That's a problem, like I'm just telling it, a string, we're not even trying to do anything with the string. It's just like, save this for later. For when we want to run the program, but apparently that's too hard, right? And this is far from the only problem with Visual Studio.

Visual Studio has many many bugs, but this is the funniest one. Because it's so simple what I'm trying to do and it can't do it all the time. This, I don't know what percentage of the time this happens. It's probably like 5%, I don't know, 4%. So then I decide to break off. Blow off some steam and play some games.

link

00:25:16

So let me download a game on the Epic store, but we're unable to start the download for some reason. So maybe I'll go to Steam, because that's a more reliable, longer-lasting store. And I'm able to actually download a game, but then when I go to the install window it's just like a black window and I have to restart Steam to play the game. Then I managed to play the game and then I all tap out for a second to check something and then now full screen is all messed up and the game's like up in the corner of a window, right?

And then I have to restart the game to get full screen again. And then I'm watching some Counter Strike there was a really good match between Cloud 9 and Luminosity gaming about a month ago. And, but for the entire match there was a mysterious sixth player on the Cloud 9 side called undefined. Up in the corner there. Let me zoom in on that map for you Counter Strike fans. Undefined is on the left. A hundred thousand people were watching this match and it was there the whole time.

link

00:26:06

I was thinking about a game I like called Ultima 4, so I went to this website that had the map. And the map was like screwed up because he was like wrapping into extra lines, so I opened a different browser to see it correctly.

I needed to get a visa to come to the Russian Federation, so I go to the visa site, and I start typing my information and, maybe, I typed out my phone number. I put the plus one and it didn't like it or something. So it says phone number is invalid over here but I couldn't fix the phone number no matter what I put in. It wouldn't accept it because whatever the variable was for phone number is invalid would never get reset. So I had to, like stop the application, close the website. Like, clear my cookies go back and reapply in order to be able to. And be very careful when I was typing my phone number. There are just so many of these. All of this was within a couple days. Like, I didn't have to try hard to find these, right? I just had to stop collecting them.

link

00:27:01

But then, I come here and as if to give me more examples in this talk. So here in this hotel where I've been writing this talk for a couple days, they have this software controlled heating and lighting system. Where it's like, you kind of push the non button buttons and things happen and some percentage of the time, not all the time, when I turn the air conditioning on or off, the phone rings.

It's not a full ring even, it's just like a little blue bubble and then it stops. But I know it's not intentional, because it doesn't happen every time. And I am NOT making this up. this actually happens in my room, right?

link

00:27:38

Now, ok, and then for this talk two hours ago, I was working at the last minute to make a diagram and I downloaded a fully legitimate licensed Creative Cloud Photoshop to my machine. The first thing I do is go to File, New Document. BAM, the new document extension could not be loaded because of a program error, right?

link

00:27:56

And so my whole point, though, is we are not surprised by any of this. My other point is that it's getting worse over time. So try this everyday yourself because we've gotten used to it. I didn't even think it would be as much when I had the idea to record this. I didn't think it would be as much as it was. Try counting for yourself just everyday, just make a little list of all these things and I think you'll be surprised how many there are.

link

00:28:22

I don't know if anyone knows what this phrase means: "five nines". I'm sure a lot of people don't. This used to be a very common phrase in the 1990s and 2000s when people wanted to sell you software or a hardware system. What it means is this system is up and working, and available 99.999% of the time, right? Four nines, would be ninety-nine point nine nine whatever. And we don't use this anymore. I think, in part, because the number of nines would be going down. And we can't make it go up again and nobody, well, certain parties, don't seem to care.

link

00:29:00

So I was, you know, working on this speech for about the past week and twice, once when I was asleep on the airplane and once the other night in the room, my laptop just rebooted while it was in sleep mode and just killed all my programs and stuff. I guess cuz it was an update, maybe it wasn't an update. Maybe it was just the operating system failing. But I think it was an update. So that automatically takes my laptop down to like three 9s or less, less than three nines. And if the laptop is less than three 9s nothing running on it could be three or four or five nines, right? So we've even lost the rhetoric of quality that we used to have, right?

link

00:29:39

And so if you say this, the software is buggy, then people like web programmers or Hacker News people or whatever, will say "Yeah, we know. But the market won't pay for it, right? Like, we could make software better. But that takes time and money to fix the bugs and all that stuff and our client won't pay for it or the market punishes that, because you take longer to get to market"

And that's true to some extent. I could definitely argue with some parts of it. But here's the thing that I'm thinking today. If you haven't seen an entire industry produce robust software for decades, what makes you think they actually can, right? They're saying we could do it if we wanted to, but we're just totally not. But, why would I believe that they actually can do it, right?

Because, like we've said there's this generational transmission of knowledge factor that I don't think is being passed along, right? So I think the knowledge of how to make things less buggy is lost. And even the knowledge of a technology company has changed and again this illustrates the difference between software and hardware.

link

00:30:49

Hardware technology companies used to be a place that makes advanced materials or defiant, you know, designs new radar or like does something but you didn't use to be able to do before, right? So now in Silicon Valley and as nearly as I could tell around the world. a software quote tech company is just a company that does stuff with computers, and is then hoping to stumble into a market niche that it can exploit. And the point is the market niche. The point isn't the software, and the point is especially not designing higher tech software that pushes the threshold of technology forward. Which is what hardware companies always used to do. And so, we've even corrupted the words tech company, right?

link

00:31:31

Ok, so now I want to bring it a little closer to what we do. There's been this sequence of abstraction that we've gone through as programmers over the decades, right? Originally, you had to program your computer in machine language, then there was assembly language, then we had the sequence of higher level languages, like Fortran and C or C++. And nowadays we have stuff like C# or Haskell or JavaScript, that are even further away from the machine.

And the justification for this is like, look that we're working at a higher level of abstraction, the higher your level of abstraction, the more you work you get done, because you don't have to worry about scheduling machine instructions and stuff. So, we're really being smart and we're saving effort. And I think that's actually true. Like, I don't think we want to program things in assembly language. That's a waste of time.

link

00:32:25

But somewhere through this chain, it becomes wrong. And that's how people are wrong a lot of the times, right? Like, you start out by being right and then you extrapolate it too far into wrong territory. But the important thing to all of this is that we only see one side of it. We see that we're being smart and saving effort, and we don't see the flip side of all of these things. Which is that there's a corresponding loss of capability, right? Because I don't program in assembly anymore, I no longer am able to program in assembly, right? If I don't, you know, if I use languages that are too high level, and have a little bit lazy, as people often are, I don't know where my variables live in memory or what they look like or even how remotely how big they are, right? I certainly don't know what the CPU is doing in response to the code that I've written. I may be scared to use non-managed languages, because the very idea of memory allocation just seems too hard and scary.

Or even if I'm a person who programs in a non managed language, maybe I'm afraid of pointers and start generating this cult of of being afraid of pointers and what to do about that, like the modern C++ people do, right? And so the rhetoric that we have is I'm being smart, I shouldn't have to do the low-level stuff, right? But part of the reality is the loss of capability that corresponds to those choices, and both of those things can be true at the same time.

link

00:33:50

I'm not saying that we're not being smart by going up some level, well a little bit. I mean there's a problem, which is at the point of going up all these levels is supposed to be to make everybody more productive. But programmers are not more productive now than they used to be. In fact, it looks to me like productivity per programmer is approaching zero. And, if that's true, then where is the proof that going up this ladder of abstraction further and further is really helping?.

link

00:34:18

So, the way to at least, you know, get a feel for this is you look at a company, like you know Twitter or Facebook. It employs a lot of people. And you look at their product and you say, how much does that product change from year to year? right?

How much functionality is added to Twitter year after year? How much functionality is added to Facebook? It's not that much, right? And then just divide by the number of engineers at the company, right? Which is thousands or tens of thousands sometimes. That's a very small number when you do that division, right? It's it's gonna be pretty close to zero. So, what's going on? Right?

link

00:34:56

And to illustrate again the difference in productivity, and that it's not just me that thinks this, I'm gonna show an excerpt from an interview with Ken Thompson, who is the original author of the UNIX operating system. And he's talking about the time at Bell Laboratories when he first started making UNIX on a computer that by modern standards had like no software at all, right?

link

00:35:22

Ken Thompson: "(At) some point I realized, without knowing it up until that point, that I was three weeks from an operating system. With three programs one a week: An editor, I needed to write code. I needed an assembler, to turn the code into language I could run. And I needed a little kernel, kind of an overlay, call it an operating system. And luckily, right at that moment my wife went on a three-week vacation to take my one-year-old, roughly, to visit my in-laws who were in California.

Disappeared, all alone and one week, one week, one week, and we had Unix".

link

00:36:24

Brian Kernighan: "Yeah, I think programmers aren't quite as productive these days as they used to be"

link

00:36:32

Yeah, he says programmers aren't productive these days like that, and everybody laughs. But it's funny, but it's not funny, right? It's really not funny when you consider, like, how much waste there must be in the difference between how productive people are and how productive they could be, if everything wasn't so messed up, right?

link

00:36:52

So I've made a case that robustness of software is declining, productivity of programmers is declining. So, if you're gonna say that actual technology of software is somehow advancing, it seems contrary to those two facts, right? So I think the argument that software is advancing is clearly false. Except again maybe in tiny local bubble-like areas.

link

00:37:14

So, now why is it so bad? Why is it so hard to write programs? Why are we so miserable when we try to write programs today? It's because we're adding too much complication to everything, right? And I have a way that I think about this called: "you can't just", right? When there's all kinds of things that you used to be able to do on a computer that you can't do today, right?

link

00:37:36

So today you can't just copy a program from one computer to another and have it work, right? You need to have an installer. Or like a flatpack on Linux, or like containers if you're a server Hacker News guy, right? And so people think this is cool. Now we have containers, that's an advantage or it's an advancement of software technology. All containers are doing is get us back to the 1960s, when we didn't have to do any of this stuff. Except it's actually not because it's adding all these steps that you have to do, right? And things you have to maintain.

link

00:38:09

So now let's think of it for a second, like, why do you need an installer to install software? Is it because of the CPU? Not really, like, imagine you have well, you know, imagine you have some x64 machine code and don't worry about how you got it into a computer's memory. But you just got it there, and you just jump to it. You set the program counter to that code. That code is going to do the same thing on a Windows PC, as it does on a Mac, as it does on a Linux machine. It does on an Xbox as it does on a Playstation 4 all, right? Because all of those systems use compatible CPUs.

So, what's the installer for? The Installer is to get around the incompatibilities that we added at the OS layer. Which is this immensely complex thing that we mostly don't want, actually. And so, we tend to think about operating systems as adding capabilities to a system, to the system of the hardware and the software. But they also remove capabilities, like, compatibility, right?

link

00:39:11

And it's often very arbitrary, and it it doesn't get any worse, than I think it does for us today when it comes to shading languages.Anyone who ships 3D engines is going to know what I'm talking about. So it used to be that if you wanted to compile a program for many platforms, you could write it in some portable language like C or C++, and you might have to do some little if Def's to modify it for the different platforms. But you could do that and it's mostly the same program. Today you can't do that because we've decided, if you're running a shader it needs to be in a different programming language on every single platform even if the hardware is the same, right?

So if you have an x86 CPU, and an NVIDIA GPU, then on one OS you need to write your shader in metal shading language and on another OS you need to write in an HLSL, right? And they're different, even though they're the same, and so you either have to rewrite everything N times, where N is large, or you have to start using Auto translation systems to rewrite your shaders and those come with a lot of complexity and annoyance and bugs. And why, though? A shader is a simpler program than the old programs that we used to write. But why have we made it harder to build a simpler program? It doesn't make any sense.

link

00:40:27

We don't care, righ? So the list of things you can't just do: You can't just copy a program. You can't just statically link. You can't just draw pixels to the screen. Oh my god, the number of steps you have to do to draw a pixel today is crazy. You can't just write a shader. You can't just compile a program on Windows without a manifest, and stuff. And on these new closed platforms, you can't just run an executable, unless it's signed through this, like, whole process, right? And all of these things, and many more that are not on this list add friction, bugs, time, engineering time, and headspace that keeps us from thinking about interesting things to actually do.

link

00:41:09

A couple of examples of this, that illustrate this isn't going to end anytime soon have entered my own life. So one of my side projects is a compiler, and to compile programs you need to link them against libraries on people's machine. Like, for example, the Windows SDK and the C runtime library. And now different versions of things, install those in different places on the machine. And so you have to like be able to find them to do the linking. And rather than make this easy today Microsoft gives you a program called vswhere which you can find on Github. And the job of vswhere is just to tell you where these libraries are installed. It is more than 7,000 lines of source code in 70 files, ok? And they didn't even try to bundle it as a library. It's a standalone program.

So what they're thinking now is you can't just make a compiler that's a standalone program. It's obviously going to be a suite of applications, and once you have a suite of applications, what's one more? What's like a little vswhere we're hanging out in there, right? They're not even thinking that this would be bad. It's crazy.

I made my own version of this based on some other people's work and got it down to like 500 lines of code. Which is still way too many to basically ask two questions, that should be two lines of code, right? So multiplier of 250.

link

00:42:28

And then, in also in the programming language world, there's this thing called Language Server Protocol, that is pretty much the worst thing that I've ever heard of. And there are just proponents of this all over. They're building systems for this right now that are going to be living on your computer tomorrow or today already maybe. And as far as I can tell, it's basically a more complicated slower way to do libraries.

So, say you've got an editor for some programming language and you want to be able to do stuff that we've been doing for decades already, like look up the declaration of an identifier by clicking on it, or tooltips that say like what type is this value, right? Well they say the way you should do that is you know you have your editor and then it's it's a hassle to make plugins, this is the made-up problem, it's a hassle to make plugins for all these different things. So in order to standardize, you're going to run a server on your machine and then your editor talks over a socket to the server and the server talks back and gives you the answer, right? Which has now turned your single program into a distributed system.

But the the flaw in this whole line of thinking, that none of these people seems to actually, like, think about at all, is that there's nothing special about, like, looking up the location of an identifier in your... That's just an API like we have all the time for everything.

So the obvious next step, if you're saying that we should architect our API's like this, is to do this for other tasks, right? So now your editors or whatever program is going to be talking to multiple of these things, and now if you ever want to author anything for this, you now have to author and debug components of a distributed system where state is not located in any central place, and we all know how fun that is, righ?t But of course libraries are not that simple, right?

Libraries use other libraries, so what happens at that point, if you're running all these servers on your system? and who don't, you know, some of them are going to like go down, and like have to restart, and, people, are synchronizing with each other. No, this is a disaster, right? And people are actively building this right now.

Alen Ladavac of Croteam has a talk at GDC and a paper about what you actually would need to do this. We just don't even have that capability which is insane, right? And yet we're spending all this effort on other things, and so this complication that's introduced into all of our systems and not only makes our lives difficult in the present when we're trying to build something, it accelerates the loss of knowledge over time, right?

link

00:45:37

So first of all there's more to know when things are more complicated, and so if you talk about a job spread among many people, each individual person knows a smaller percent of what they need to do. They have a less global view which makes it harder to do good work, right? And harder to transmit their knowledge on to people in the future. Another thing that happens is that deep knowledge becomes replaced by trivia.

So deep knowledge might be a general concept, like, here's how cache coherency works and that enables software to run fast on, like, different processors and stuff. And trivia is something like, well this sprite in Unity doesn't display properly for some reason, but we know we can fix it if you open this panel and toggle this boolean, and that fixes it for a while. But then some weeks later, for random reasons, the boolean mysteriously untoggles. So just make sure to check that before you ship and it'll be fine, right? And the reason that's trivial, is not only because it doesn't apply to anything else in the world. But it's also going to be outdated in six months when the next Unity comes out. And it's just offensive that we're spending our brainpower on these things, okay?

link

00:46:43

And the third thing that happens is good information is drowned by noise. So if something is really hard to understand, the percentage of people who put the effort into understanding it is going to be small, and the harder it is, the smaller that percentage. And so if you ask people, or you learn at a school, or you search on the web, your probability of getting a bad answer to the problem is much higher for more complicated things, than it is for less complicated things. And so the complication propagates and magnifies.

link

00:47:15

So let's get back to this collapse of civilization stuff, right? The more complexity we put in our system, the less likely we are to survive a disaster, right? Because we have to maintain all that complexity. We're acting right now, like we believe that the upper limit of what we can handle is infinity amount of complexity, right? But I don't think that makes any sense.

So what's the upper limit? how would we decide how much complexity we can handle? And that's different from what people today actually can handle. So if you have an engineer who can hold a whole system in his head that's really complicated and work on it. When that guy quits and needs to pass on his job to somebody new, he's not necessarily going to be able to communicate all that, right? So the amount of complexity we can sustain over time, is less than the amount of complexity that individuals can do today, right?

link

00:48:05

So why am I talking about this at a games conference, right?

Like, everybody knows that games aren't serious and whatever, right? But video games at least used to be about maximizing what the machine could do, and, like, really impressing the people playing the game. And maximizing the machine means you have to understand the Machine very well. And that correlates with robust software, because if you understand the machine well, you're less likely to make the kind of bugs that come from misunderstanding. There's anti correlations with robust software too, but, anyway, now we're not really about that so much.

Especially talking about independent developers. People are shifting to Unity and Unreal and must, right? Not very many people write their own engines anymore. So we have entire generations of programmers who have grown up learning to program by, you know, making little C# snippets that just plug into other parts of Unity or something. And they've never written something systemic, and they've never written something low-level.

Which on the one hand is fine, like, I'm not saying we shouldn't do that. Because there's a degree to which it's smart, it reduces development time, right? It helps you ship your game sooner. But, like I said before, there's a flip side. That flip side is giving up the capability of doing the other thing. Giving up the knowledge of how to do the other thing.

So I don't think it's bad in isolation if a lot of people make games where they just put snippets into Unity, right? But if everybody does that, then nobody knows how to do anything but that. And then after a while what's gonna happen? Because we're assuming that we'll just be able to use these engines forever.

But Unity and Unreal were created in an environment where there were lots of people at games companies making engines all the time, right? And that's where they hired people from, and when there's no longer a natural way to learn how to make engines, because nobody does it, where are Unity and Unreal gonna hire employees from to maintain those engines that everybody's using? Right?

And you know to the extent that they can hire people, is the quality of people gonna go down because they have less experience. It just takes a long time to ramp up, right? So then maybe at some point, well, certainly at some point there's not enough people to make a new competing engine. But maybe even at some point you can't really maintain the old ones and they just keep decaying over time, that can happen.

link

00:50:37

And so the way I used to think about game developers is, kind of like the Foundation in the Asimov books where we kind of knew how to really program computers and, you know, also some other kinds of programmers like embedded systems people, and high performance computing people, all sort of knew what was going on with computers and after the rest of software just kind of decays and falls apart, we still have the knowledge and we could bring it back and give it to people.

But I'm not really sure that that's gonna happen now. Because I just don't know, I mean, I don't know if there will be enough of us doing low-level work, or even people doing high-level work who understand what's happening at the low-level while they do the high-level, right? So, maybe there needs to be a second Foundation. Spoiler alert for anyone who hasn't read the book.

link

00:51:23

So back in the Bronze Age, right? One of the reasons those civilizations disappeared, is that the way things were set up was that reading and writing was only done by a small elite class who went, you know, went to school for years, and this was protected. The public couldn't know how to do this, they probably mostly didn't want to know. And because those skills weren't widespread they were fragile, so when the society was disrupted they weren't continued because not enough people could carry it forward.

link

00:51:53

Today, almost nobody knows what's happening on a CPU, right? That skill is not widespread. So it's fragile and so do we think that this immensely complicated thing that we've built today is somehow more robust than what they had in the Bronze Age with just making bronze, because that didn't survive. If that didn't survive, why do we think what we're doing now is gonna survive? Right?

link

00:52:17

And we might have some similar stressors, we might have some climate change issues, right? Or you might have some new stuff, like what happens if there's so many cyber attacks that countries just start cutting each other off the internet? Right? Now lots of people in lots of countries can't get to StackOverflow to figure out how to copy and paste their code, so their code production is impacted, right? or what happens if China just says: "you know what?, we're just gonna keep all the CPUs, now we don't want to sell you any"? What's gonna happen, right? None of these things in isolation, I don't think, will bring down civilization. But it can certainly hit the system with a big shock. And if the system is too complex, it may not survive that shock very well. And so I'm just trying to say, like Elon Musk was saying, the technology by itself will degrade and we need to, as soon as we can, start working against this, right?

link

00:53:09

At every level that we have access to, we have to simplify the hardware we're running on. We have to simplify the operating systems we use, the libraries we use, the application code we write, the communication systems we do this over, like the internet. We have to simplify how we compile, debug, and distribute software. And we have to simplify how people interface with software. And that sounds like really a lot of stuff to do, but the good news is that all of these things are so ridiculously complicated right now, that it's very easy to find things to improve. Simplifying any of these systems only requires the will to do it, rather than a taste you have to have a taste to recognize how complicated things are and how they would be better if they weren't so complicated, ok?

link

00:53:54

Now a lot of people are probably like ok, whatever. Software is complicated, but I don't believe civilization is gonna collapse or anything. And so you know maybe, maybe, but I would say if you're a programmer, you should care about this anyway because even just your own personal future.

Like programmers are not that happy today, we're often very grumpy, and the reason we're grumpy is because we're doing stupid things all the time, instead of interesting things. And that's not gonna get better if we keep doing things the way that we do them, right? So you personally will be happier if we change the way we do things, and if we do things the way they are now, maybe the future is deeply mediocre in the way that America's space future was going to be deeply mediocre.

link

00:54:41

Now, even if you just want to survive as just an individual game developer like you're thinking look I just want to get my game done I want to ship it, I want it to succeed financially, even if you just want to have a very limited scope of concern like that, removing complexity is still the right short-term play, even if it doesn't seem like it.

I'm sure we all are very familiar with cases like, well we're gonna ship in five months and we're having a lot of problems with this particular system, it's really buggy, you know. It loses people's work all the time, whatever. But we just have to stick with it for five months and it'll be passed, it'll be history and that's good because rewriting it would be a lot of effort. It might delay shipping, and so we're gonna stick with it, we're gonna stick out the five months and that's always wrong.

Because always what happens is it takes two years to ship instead of five months, and so the amount that you suffered from the system is way worse than it otherwise would have been. And maybe in fact, that system was a large ingredient in why it took so long to ship.

So, simplify and in simplifying your owncode to solve your own local problems you're also building institutional knowledge about how to simplify. Which sounds really basic, but I would claim we don't even really have that anymore.

link

00:56:05

Here's some references of videos you can watch if you're interested in this kind of topic: Casey Muratori video "The 30 million line problem". Samo Burja video: "Civilizations: institutions, knowledge and the future". And the Eric Cline's video which I showed snapshots of earlier: "1177 BC, the year civilization collapsed".

And that's all I have to say for now. Thank you for your time.